Abstract

Studies primarily involving single health professions programs suggest that holistic review in admissions can increase underrepresented minority (URM) representation among admitted students. However, data showing little improvement in the overall proportion of URMs in many health professions, despite widespread use of holistic review, suggest that relatively few programs using holistic review admit substantial proportions of underrepresented minorities. Therefore, more research is needed to understand factors that facilitate holistic review practices that successfully promote diverse student enrollment. The literature suggests that a supportive organizational culture is necessary for holistic review to be effective; yet, the influence of culture on admissions has not been directly studied. This study employs a qualitative, multiple case study approach to explore the influence of a culture that values diversity and inclusion (‘diversity culture’) on holistic review practices in two physician assistant educational programs that met criteria consistent with a proposed conceptual framework linking diversity culture to holistic admissions associated with high URM student enrollment (relative to other similar programs). Data from multiple sources were collected at each program during the 2018–2019 admissions cycle, and a coding manual derived from the conceptual framework facilitated directed content analysis and comparison of program similarities and differences. Consistent with the conceptual framework, diversity culture appeared to be a strong driver of holistic admissions practices that support enrolling diverse classes of students. Additional insights emerged that may serve as propositions for further testing and include the finding that URM faculty ‘champions for diversity’ appeared to strongly influence the admissions process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Disproportionately high rates of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19) infection and related deaths among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States shine a spotlight on the urgent need to address pervasive and persistent health disparities. The issue is complex; disparities result from an array of interrelated factors including adverse social determinants of health and societal racism as well as implicit bias among healthcare professionals (Owen et al., 2020). While there are no straightforward solutions, increasing the number of underrepresented minority (URM) healthcare providers has long been recognized as one way to improve the quality of care minority and underserved patients receive (Cohen et al., 2002; Mitchell & Lassiter, 2006; Sullivan, 2004). Minorities underrepresented in the U.S. health workforce relative to the general population include Hispanics/Latinos (all races), African Americans, American Indians or Alaskan Natives, and Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders (Health Resources & Services Administration 2019). African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos, for example, comprise just 8.2% and 7.6% of the physician workforce respectively, compared to 13.4%, and 18.3% of the general population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019; U.S. Department of Labor 2019). Over the last decade, health professions educational programs have widely adopted holistic review admissions practices as one means to increase diversity among students (Urban Universities for HEALTH, 2014). Although the existing literature suggests that holistic review is effective, much of the evidence for its association with increased URM enrollment stems from evaluations involving a single institution or small numbers of programs (Felix et al., 2012; Grabowski, 2018; Wells et al., 2011; Witzburg & Sondheimer, 2013; Wros & Noone, 2018; Zerwic et al., 2018). Findings from one large 2013 national survey of 228 publicly-funded health professions schools showed that a high percentage of schools—including 93% of dental and 91% of medical schools—self-identified as using holistic review, and a majority using it reported increased diversity among students (Urban Universities for HEALTH, 2014). Yet, in recent years, despite an increasingly diverse U.S. population, URM representation among dental and medical students nationally has not substantially increased (Lett et al., 2019; Slapar et al., 2018). Assuming numerous health professions programs do in fact use holistic review, the collective national data suggest that many of them do not admit significant numbers of URMs.

The apparent discrepancy between widespread use of holistic review and little if any overall progress toward increasing proportions of URM students also exists in the physician assistant (PA) profession. Created in the late 1960s mainly to address physician shortages in rural communities, PAs, like nurse practitioners, have been increasingly relied on to care for medically underserved patients, who are disproportionately racial and ethnic minorities (Physician Assistant History Society, 2017; Proser et al., 2015; Shin et al., 2013). Therefore, a diverse PA workforce may be particularly important. Until the 1990s, PA programs educated higher proportions of URM students than other health professions programs like medical schools (Mulitalo & Straker, 2007). In recent years, however, the proportion of URM PAs has remained stagnant. As of 2019, only 7.6% of first-year PA students were Hispanic/Latino and just 3.9% were African American (Physician Assistant Education Association, 2020).

In 2017, this paper’s first author, BC, conducted a survey of PA educational programs and found that 77% reported using holistic review in admissions. The survey was distributed by the national Physician Assistant Education Association (PAEA) and included responses from 99% of the 223 U.S. PA programs accredited at the time. Results included a modest positive association between use of holistic review practices and percentage of URM first-year students (Coplan et al., 2021). However, the association was largely driven by high percentages of URM students admitted to a relatively small number of the programs using holistic review. This finding, which served as a main impetus for the current study, raises the question: Why are some programs that use holistic review so much more successful at achieving diverse student enrollment than others?

Holistic review refers to a mission-driven selection process that incorporates balanced consideration of applicants’ experiences, attributes, and academic metrics (Association of American Medical Colleges n.d.). Model holistic review practices—which are based on four core principles shown in Table 1 include developing a mission statement for admissions that includes diversity as an essential goal and evaluating non-academic criteria related to a program’s mission as part of the initial application screening process (Addams et al., 2010). A main objective of holistic review is to encourage diversity (Association of American Medical Colleges n.d.). Additional guidance for adopting holistic review emphasizes the need for a comprehensive approach to improving diversity that involves outreach and recruitment and evaluation of diversity-related outcomes (Addams et al., 2010; American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2016). It is important to note that diversity encompasses the range of human differences, including attributes related to socioeconomic status, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, geography, disability, and age. Accordingly, holistic review may incorporate consideration of a broad range of diversity- as well as mission-related factors (e.g., commitment to service in an underserved community) and personal characteristics (e.g., leadership qualities or experiences with adversity). However, due to the persistent lack of URM representation in the health workforce, discussions of holistic review often focus on increasing the numbers of racial and ethnic minority students (Addams et al., 2010; Coleman et al., 2014).

A potential barrier to successful adoption of holistic review is the absence of an associated conceptual framework (Artinian et al., 2017; Glazer et al., 2016). Furthermore, health professions educators have called for more resources to assist them, including case studies involving successful practices (Artinian et al., 2017; Glazer et al., 2016). Several articles describe individual program experiences with holistic review; however, a framework has not been tested. Another factor that may limit the utility of holistic review is a failure to appreciate the influence of organizational culture. In their review of interventions to enhance diversity in medical schools, Vick and colleagues (2018, p. 57) note that, among the principles to improve diversity, culture is the one most often neglected. Moreover, the need for a supportive organizational culture—in other words a culture that values diversity and inclusion (or ‘diversity culture’)—is often mentioned in articles about holistic review (DeWitty, 2018; Glazer et al., 2018; Wros & Noone, 2018); yet, the influence of culture has not been specifically examined. The purpose of this study was to enhance understanding of effective holistic review by exploring the role diversity culture plays in the holistic admissions process at two PA programs (or ‘cases’) with high URM enrollment (relative to other programs using holistic review). A conceptual model (described below) was used to help create a picture of diversity culture in practice and generate insights useful to health professions programs seeking to meaningfully improve diversity through admissions.

Conceptual model

The conceptual model was derived from the literature on holistic review and from Schein’s concept of organizational culture (see Fig. 1). Schein (2017, p. 6) defines culture as

[…] the accumulated shared learning of a group as it solves problems of external adaptation and internal integration; which has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, feel, and behave in relation to those problems.

While various definitions of culture exist, nearly all include the notion that shared beliefs and assumptions (e.g., underlying values) drive behavior (Schneider et al. 2013; Scott-Findlay & Estabrooks, 2006; Tierney, 2011). Schein’s model of organizational culture was selected because it provides a practical framework for culture examination. According to Schein (2017), culture exists in the context of three levels: (1) basic underlying assumptions, (2) espoused beliefs, and 3) artifacts. Shared basic assumptions constitute the deepest, ‘taken-for-granted,’ level of culture that directs attitudes and behavior. Insight into these basic assumptions can be derived from the next level of culture—espoused beliefs—which include stated values and goals (e.g., a mission statement). Culture also manifests in artifacts—such as displayed photos and observable ceremonies—which comprise the most superficial and visible level of culture. Schein (2017) cautions, however, that although artifacts and espoused beliefs provide insight, an appreciation for the basic underlying assumptions requires assessing whether attitudes and behavior are consistent with the more superficial levels of culture. In other words, a discrepancy may exist between espoused culture (e.g., what is stated) and enacted culture (e.g., what is done). A germane example of the potential divergence between layers of culture is a university that attests to the value of a diverse learning environment but does not have a diverse faculty or student body.

Creating a mission statement for admissions that promotes diversity is recommended as an initial step for conducting holistic review; however, a mission statement may or may not accurately reflect basic assumptions that guide behavior. The conceptual model for this study depicts an organizational culture in its entirety (i.e., all three levels) that values diversity and inclusion (i.e., diversity culture) as the primary mechanism for effective holistic review (see Fig. 1). Additionally, the model shows that culture influences the determination of outcomes a university or educational program deems important enough to measure (Tierney, 2011; Zheng et al., 2010). Through its influence on attitudes, culture also affects how people enact practices designed to achieve outcomes (Zheng et al., 2010). In the case of holistic review, for example, culture may affect how low socioeconomic status is evaluated—as a weakness or a strength. The model also demonstrates the typical relationship between organizational practices and outcomes, whereby practices are reinforced or revised in response to performance on outcome measures. Based on this case study’s findings, a depiction of the effect diversity-related outcomes (e.g., increased numbers of URM students) can have on organizational culture, such as strengthening appreciation for diversity, was added to the preliminary model (using a dotted line). The model’s underlying hypothesis is that, while mission-driven admissions practices are useful, in terms of increasing URM enrollment, holistic review is most effective when it is culture-driven.

The proposed conceptual model served as a foundation for a novel approach to studying holistic review. Rather than focus on a transition to holistic review and associated outcomes, this study examined two PA programs that had already achieved high URM student enrollment. The goal was to enhance understanding of the potential influence of diversity culture on effective practices. The central research question was: How is an organizational culture that values diversity and inclusion (diversity culture) manifested in holistic review practices that achieve high URM student enrollment? Sub-questions were: (1) What specific admissions practices do programs that enroll high proportions of URM students use (e.g., for initial applicant screening)? and (2) How are these practices supported?

Methods

Design

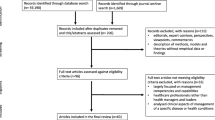

A qualitative, multiple case study approach involving two instrumental cases was used to facilitate analysis and comparison of effective holistic review admissions practices (Crowe et al., 2011; Yin, 2018). Instrumental cases are theory-dependent, seen in relation to other cases and examined in the “all-together,” as unique collections of inseparable variables (Sandelowski, 2011, p. 158). Case study methodology focuses on intensive examination of data from multiple sources to gain in-depth understanding of a phenomenon in natural settings and is therefore ideal for studying complex concepts like organizational culture (Sandelowski, 2011; Yin, 2018). Additionally, case study lends itself to pragmatism, which, as our guiding orientation, allowed for flexibility in our approach to collecting data and conducting analyses that would best address our research question (Creswell & Poth, 2018). Due to the nature of intensive inquiry, case study research often focuses on a single case (Miles et al., 2014; Sandelowski, 1996; Yin, 2018); thus, statistical generalizability may be limited. However, investigating large numbers of cases can impede thorough analysis and threaten the integrity of the methodology (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Sandelowski, 1996). Therefore, we analyzed two cases. This decision allowed for in-depth analysis while enabling cross-case comparisons and replication of findings that enhance transferability of findings to other settings (Miles et al., 2014). Moreover, case definitions (described below) were constructed so that the conceptual model linking diversity culture to holistic review practices that achieve high URM enrollment could be qualitatively tested. Thus, we were able to generalize findings to a theoretical understanding of the issue under study and apply generalizations (also called assumptions or propositions in qualitative research) derived from the findings across cases, which strengthens trustworthiness and further promotes transferability (Horsburgh, 2003, p. 311; Miles et al., 2014).

Sample and setting

We chose two ‘best possible’ cases, that best exemplified diversity culture and holistic review practices associated with high URM student enrollment. These cases provided an intensive “opportunity to learn” about the phenomenon of interest (Stake, 2008, p. 130) and increased transferability because they varied with regard to factors that may serve as alternative explanations for high URM attendance (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

Responses to questions contained in the 2017 survey of PA programs discussed in the introduction were used to identify programs (i.e., cases) that met criteria for best possible cases. Criteria derived from the main principles of holistic review were that programs must have: (1) indicated they use holistic review; (2) responded affirmatively to three questions that assessed commitment to diversity, including having a mission that supports diversity; and (3) reported that use of holistic review was associated with increased racial and ethnic diversity among students. Additionally, programs must have enrolled a proportion of URM first-year students that was at or above the 90th percentile for all programs using holistic review. Percentiles were determined using a ratio of program first-year student demographics to a program’s regional population demographics (e.g., percentage of Hispanic students in a program located in a regional division of the U.S./percentage of the Hispanic population in that regional division of the U.S.) (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016). This ratio was used to account for the influence of population demographics in PA program locations, which have been shown to moderately correlate with URM enrollment (Coplan et al., 2018).

The aforementioned survey of PA programs was used to identify seven programs—three public and four private—representing best possible cases, whose identities were only known to PAEA, the national organization that distributed the survey. To maintain program anonymity, a PAEA staff member sent email invitations to the program directors of all seven programs on behalf of the researchers, who offered a $2000 honorarium for study participation. Four programs expressed initial interest. To strengthen transferability, we selected maximum variation sampling, using parameters such as public versus private funding and different geographic location (Creswell & Poth, 2018). Ideal maximum variation was not achieved on these parameters; however, other characteristics that may influence URM enrollment, for example degree of minority representation among faculty (see Table 2) varied across cases, maintaining the integrity of the selection criteria and study methodology. The two cases selected—both private, nonprofit programs in the same regional division of the country—demonstrated the greatest willingness and ability to allow researcher access to their inner workings, which is essential for case study research (Sandelowski, 2011; Yin, 2018). It should also be noted that 62% of PA programs are housed in private, non-profit institutions (Physician Assistant Education Association, 2020).

Data collection

After obtaining Arizona State University Human Subjects Institutional Review Board approval, we collected data from a variety of sources: (1) texts and artifacts, such as information from websites and admissions materials, (2) semi-structured interviews, using a protocol derived from the conceptual framework, pilot-tested, and revised for clarity, (3) formal and informal observations using a worksheet to capture organizational characteristics and processes for applicant selection, and (4) a focus group of URM students at each program (see Table 3). The semi-structured, pilot-tested student focus group protocol focused on students’ reasons for selecting their program as well as their perceptions of the admissions process and program culture. After collection, all focus group and interview data were anonymized and transcribed.

To complete the study’s field research, BC visited each program for four days during the 2018–2019 admissions cycle, when knowledge of the admissions process would be fresh in study participants’ minds. At each program she was given a tour, observed one faculty meeting where admissions-related topics were discussed, and conducted the focus group of URM students. At both programs, seven first-year URM students, an optimal number for focused discussion, participated (Morgan, 1997). An overview of individual interviews and additional sources of data from each program are listed in Table 3. During the program visits, BC remained onsite during ‘off-times’ to familiarize participants with her presence and minimize their sense of intrusion. Remaining onsite also provided opportunities for informal observations and impromptu discussions.

Data analysis

Directed content analysis, which is a strategy used to examine a phenomenon for which existing theory may be underdeveloped, was used to evaluate the data (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). To facilitate this process, existing literature and theory were used to create an initial list of codes, which are labels attached to portions of text (or units of meaning) to designate themes (i.e., subjects that appear with regularity in the data). These start codes/themes were then used to guide initial data analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). A codebook, developed a priori, organized codes into five domains derived from the conceptual model (Colorafi & Evans, 2016) and phrased codes as gerunds, which are words ending in ‘-ing’ that signify observable or conceptual action (Miles et al., 2014, p. 74). Using the codebook, study authors initially team-coded the data, making revisions or adding new codes to reflect themes or domains that were not captured within the initial codebook. Next, the revised coding scheme was used to re-code interview data and further refine the codes. The reliability of the final coding scheme was evaluated by assessing interrater domain agreement (Kappa = 0.89 [95% CI, 0.82–0.97]). The finalized codebook was then used to complete a thematic analysis of Case 1, and the approach was repeated for Case 2, which is a replication tactic used to assess for congruent patterns (Miles et al., 2014; Yin, 2018).

The interview codebook was also used as a basis for thematic analysis of student focus group data. Additionally, new codes were added to identify themes reflective of student reasons for choosing to attend their respective program. Focus group data for each case also were analyzed sequentially, applying the revised coding scheme derived from analysis of Case 1 to Case 2, thereby assessing for common themes and patterns (Miles et al., 2014; Yin, 2018). Interrater domain agreement for Case 2 was also assessed (Kappa = 0.92 [95% CI, 0.86–0.99]). Analysis of observational and artifact data was primarily conducted using analytic memos, which are narratives that record the researcher’s thoughts and enhance and maintain transparency in relation to data interpretation (Miles et al., 2014, p. 95). During a final phase of analysis, data from each case were organized into matrices, or data displays, to facilitate the classic techniques of case study research: within-case and cross-case comparisons of similarities and differences, development of propositions for further testing, and additional evaluation of data relevance to the conceptual model (Crowe et al., 2011; Miles et al., 2014).

Methodological integrity is maintained in this report through grounding in the meaningful, contextual, and coherent evidence provided by the case study report format, attention to transferability in the study design, and acknowledgement of investigators’ perspectives (Levitt et al., 2018). Neither study author identifies as URM; both have worked extensively in clinical and educational settings with URMs and have experience with holistic review. Through their experiences, both authors became accustomed to challenging their own assumptions and identifying issues of power and privilege. In addition to using holistic review, BC has participated in standard admissions processes and has published research on diversity in the PA profession. The study’s second author, BE, used holistic admissions at the baccalaureate and PhD levels in nursing for well over a decade, has published extensively on educating diverse populations, and is a federally funded mixed-methods researcher studying caregiving Mexican–American families.

Findings: within-case analyses

Below, we present a description and analysis of each program in the context of the conceptual model (see Fig. 1). We use pseudonyms to maintain participant anonymity and have withheld details that may reveal program identity.

Case 1: recent holistic review adopter

Program 1 description

Program 1 was established in the 1990s at a private, nonprofit university that only offers degrees in the health sciences and is located in an urban area with a diverse population. The university as well as the program mission statement includes a commitment to diverse communities. A large majority of program faculty are non-Hispanic white; however, minorities comprise a majority of university and program staff. Program admissions requirements include paid or volunteer healthcare experience and PA shadowing. No standardized examination (e.g., Graduate Record Examination [GRE]) is required. The average overall GPA of admitted students was slightly below the 2016–2017 national average of 3.57, and total tuition was higher than the national average of $87,160 for private programs. Additional program characteristics are listed in Table 2. Program 1 intentionally revised its admissions process in 2012 due to faculty dissatisfaction with class diversity (in 2010, the class had no African American or Hispanic/Latino students) and in response to a university-wide effort to increase URM enrollment.

Diversity culture

Although case selection criteria (which included responses to survey questions) aimed to identify PA programs with stated commitments to diversity, a more thorough evaluation was necessary to gain a true appreciation of culture (Schein & Schein, 2017). Consistent with diversity culture, artifacts and espoused beliefs at Program 1 reflect a strong appreciation for diversity and inclusion, as well as a commitment to service. Webpages and brochures prominently display students, faculty, and patients from diverse backgrounds and consistently highlight service in diverse communities. These more superficial reflections of culture were in turn supported by student, staff, and faculty attitudes, behaviors, and actions. Data collected from the URM student focus group and from observations, for instance, reveal that students experience a sense of inclusion and support within the program. For example, they discussed “how family-oriented it is, how inclusive everyone is,” and remarked that “the culture is all about supporting one another, empowering one another, and supporting the community.” They also agreed that seeing “people who look like me” helped them determine that the program’s publicized diversity was authentic.

Attitudes reflective of tolerance and appreciation for every individual’s inherent value were consistent among faculty, who frequently mentioned applicants’ and students’ unique ‘stories.’ The program’s director for 11 years, ‘Nick,’ has been with the program for 20 years. During the observed admissions interview day, he praised faculty members—whose average tenure at the program (13 years) is more than twice the national average—and highlighted the program’s many community service activities. He went on to welcome interviewees with the statement, “We value you, your presence here, and your time.” Matriculated students appreciated his desire to “[hear] us out as people” and recalled him sitting down with them to ask, “‘Okay. How are you guys feeling? What do you guys need from me to succeed?’”.

Nick’s attitude is also reflected in his substantial efforts to improve diversity within the program which include: facilitating the program’s more holistic admissions process, instructing faculty to utilize more URM guest lecturers, and recruiting URM faculty. In fact, just prior to the study visit, the program hired its first African American faculty member.

In addition to leadership, a potentially important aspect of Program 1’s culture is that the level of commitment to diversity appears to have been increasing in recent years, although not without some challenges. Students and faculty uniformly expressed a feeling of inclusion and support within the program; however, faculty and staff seem to be experiencing a slow but positive shift in university culture that one staff member described as “definitely diverse” and “moving towards inclusive.” Both faculty and staff believed that university resources to support the increasing numbers of minority students were not yet sufficient. Notably, the impact that the diverse student body is having on the culture as well as the curriculum was mentioned several times.

‘Dee,’ Program 1 staff interview: The student body is very social justice-oriented as a whole. They're driving and forcing faculty to shift and change, right, and the school to shift and change. So it's more inclusive than when I got here 15 years ago, far more inclusive. I feel way better about being on campus as a person of color these days. I feel like we have great conversations, we have hard conversations, we have very uncomfortable conversations. And we create really safe spaces to make that all happen.

The circumstance described below was noted by three faculty and one staff member, all of whom viewed it as a positive occurrence.

‘Katie,’ Program 1 faculty interview: One thing that a student brought to our attention was more representation of people in color in our PowerPoints. This is just fresh […] a couple months ago and she actually brought it up to me in advising and she did speak to our diversity center here on campus about it. So that became a good faculty conversation and I wholeheartedly agreed with her. She's like, ‘What does a blue dot sign look like?’ It's a physical diagnosis kind of sign. ‘What does a blue dot sign look like on a black person? Or do you even see that? What does a melanoma look like on, every slide and every PowerPoint is Caucasian skin.’ And so I thought that was an excellent point.

Program practices

Admissions

When Program 1 revised its admission process in 2012, faculty weren’t aware they were creating a ‘holistic review’ process. That said, the practices they now use reflect core principles of holistic review (see Table 1), with the exception that the process has been aligned with re-evaluated program values as opposed to a specific mission. Additionally, the program has relied, in part, on a faculty key informant or ‘champion for diversity.’ Non-academic metrics related to experience and background are considered as part of the initial screen of applicants, and the overall process is intentionally design to create a diverse pool of interviewees and accepted candidates that includes URMs.

As part of re-visioning the program’s admissions process, Nick (the program director) recruited a ‘champion for diversity’: ‘Umberto’—a Latino pediatrician who is a first-generation college graduate and founder of a successful network of pipeline programs. Umberto led “… soul searching within the department about our admissions process to try to identify the part of our admissions process that favored a majority group …” and helped re-evaluate program values, particularly with regard to clinical experience.

As someone dedicated to service and actively involved in supporting youth from diverse backgrounds, Umberto serves as a source of insight, vision, and connection to diverse communities. His discussion of revising the admissions process, supported by faculty interview data, illustrate his influence.

Umberto, Program 1 faculty interview: When we restructured those values that were more humanistic and more about interfacing with people and working with people, then that opened it up to a lot more different jobs and volunteer experiences. Patient educators, working at community-based organizations, mobilizing people, all of that. A lot of those experiences that a lot of kids of color come in with because that's their values. That made it less stringent upon clinical experience and academic standards. Although we still value them and we score it, it wasn't just about that.

‘Uma,’ Program 1 faculty interview: It used to be before [Umberto] came onboard, it was pretty much all just GPA and healthcare experience and that was pretty much it, and when we really looked at what's important to us, we can teach medical knowledge, we can teach some of these—like we can teach skills. What do we really want them to get out of healthcare experience? We’re really looking for the exposure to the profession, and really it's about teamwork and communication.

During the re-visioning process, faculty came to consensus around valued criteria and revised the matrix used to evaluate applicants—which now includes scoring more types of experiences and placing greater weight on valued attributes—and incorporated consideration of most recent academic performance (i.e., last 60 credit hours). Additionally, a few years ago, the program added supplemental questions to the centralized national PA program application that ask applicants to describe how their background and experiences align with the program’s core values and to explain any academic deficiencies. Perhaps more importantly, interview data suggest that faculty thoughtfully consider responses to these questions: “…you learn a ton about the applicant. Like, ‘my mom was diagnosed with breast cancer my freshman year in college and I was her primary caregiver.’ You know, these stories that make me go, oh, no wonder you got a 2.9.”

Although faculty noted that they share program values such as tolerance and appreciation for diversity, they also contribute individual viewpoints to the admissions process. For example, some faculty focus on healthcare experience or GPA more than others do, but they collectively acknowledge the need for resilience, community-mindedness, and appreciation for the PA role. Faculty also consider feedback from current students, alumni, and adjunct faculty who participate in the program’s unique day-long admissions interview experience. Groups of candidates rotate through multiple stations, participating in individual interviews with faculty, a team decision-making activity evaluated by alumni, and, among other things, an informal discussion conducted by a panel of current students. Students also serve as greeters and guides throughout the day, which is structured to provide opportunities to evaluate candidates in different situations and generate feedback from multiple perspectives.

Outreach and recruitment

Program 1’s university Office of Diversity and Inclusion (ODI) organizes numerous outreach and diversity-related activities throughout each year. University students are encouraged to attend and participate in a program that provides financial support for those who regularly take part in community and on-campus events designed to engage youth from diverse communities. Each PA program cohort has a ‘service chair’ to help facilitate community service activities, and several PA students serve as mentors to local high school students involved in the pipeline program founded by Umberto, who noted that mentoring “…is a lovely way where many of our minority students feel that they are giving back and bringing up the next generation.” Program recruitment activities include regular online and on-campus informational sessions. Additionally, the ODI specifically invites students who unsuccessfully applied to the PA program to an on-campus event involving current URM students that focuses on ways to strengthen their applications.

Academic support

Program 1 faculty are aware that students from diverse backgrounds may face unique challenges. For example, two faculty members discussed the difficulty students whose first language is not English can have finishing exams, because translating in one’s head takes extra time. Moreover, the program reaches out to students after an initial exam failure and provides several means of informal and formal support to ensure academic success, including instruction on test-taking strategies; the services of a writing specialist, tutor, or counselor; and meetings with faculty. They “…pull out all of the stops because the earlier you catch them, the better.” Despite faculty commitment to these efforts, several discussed the need for more resources.

Umberto, Program 1 faculty interview: [We] realized, that if we were going to open up our program to students who perhaps weren't as well prepared academically or may potentially pose a challenge, that we as an organization had to make sure that we responded. In some ways, that's something we still need to work on. It has challenged us. The fact that we have diversified our cohort so much has helped us to define where the gaps are in our support system.

Faculty acknowledged that the ability to support students can affect selections decisions.

'Ugo,' Program 1 Faculty interview: When we're agonizing over [an applicant] who doesn't quite have the grade point average in looking at their academic record and it's making us wonder, are they going to fail anatomy? Are they going to fail courses? […]. What could we do if we take the stretch and admit them to make sure that they succeed? What are the resources?

Outcome measures

To explore the specific relationship between outcome measures and admissions, we chose to ask faculty and staff about how they determine whether an admissions cycle has been successful and how they respond when admissions outcomes are not achieved. Faculty discussed typical approaches, including monitoring academic performance (e.g., course grades, Physician Assistant National Certifying Exam [PANCE] pass rates) and professional behaviors of cohorts. They also look back to determine if any admissions criteria correlate with poor academic performance, although none have been identified. In addition, several faculty discussed informally assessing the diversity composition of cohorts, not only with regard to racial and ethnic diversity but also gender, age, and socioeconomic diversity. The influence of this assessment is perhaps best illustrated by the program revising its admissions process in 2012 in response to poor URM student enrollment.

Case 2: mission-based holistic review

Program description

Established in the 1970s, Program 2 is among the oldest PA programs in the U.S. It is administratively housed in a private, nonprofit medical school but physically located on a separate campus that, like Program 1’s campus, is in an urban area with a diverse population. Program 2’s medical school and university do not include diversity in their mission statements; however, the program itself was created with an express mission to serve medically underserved communities and educate students from diverse backgrounds. Requirements for admission, which are shown in Table 2, include completion of the GRE or Medical College Admission Test® (MCAT), although the scores are not heavily weighted. In fact, the program is considering eliminating the standardized exam requirement. Paid clinical experience and PA shadowing are preferred but not required. The average overall GPA of admitted students was slightly below the national average, and total tuition was higher than the national average for private programs. The program has engaged in mission-based holistic review of admissions applications for multiple decades.

Diversity culture

Program 2’s diversity culture is grounded in its mission. Program artifacts and espoused beliefs—including a program magazine; student-led website; and program celebrations, such as African American Day—uniformly reflect a commitment to diversity, inclusion, and service in medically underserved communities. Faculty, staff, and student attitudes—which provide insight into the deepest level of culture—consistently demonstrated an appreciation for the program’s mission, and faculty and staff expressed satisfaction with the ways the university and medical school, in particular, promote diversity and provide support for the program’s diversity-related pursuits. Interviewees articulated the program’s long-term commitment to its diversity-focused mission “….because of where we are, who we are, how the program has evolved over the years, and the belief of the faculty and leadership.”

Students reported feeling supported at the program and remarked on the influence of their diverse faculty.

‘Alexis,’ Program 2 student focus group: The diversity of the faculty really hit me because I went to [University] for undergrad and I've never had a diverse faculty member my entire four years there. So when I came here, I was like, ‘What, there's a Latina PA, who's [working in] family medicine, ER, a bunch of stuff.’ So I was just like, ‘What? What's going on?’ I was never used to that. That's why I never connected with the professors over there, I don't know, because of that maybe. So I never went up to them, I was like, I'm gonna’ do this on my own. That's how I've done it all the time, so I'm just gonna’ continue doing it on my own. [Though] here I actually feel comfortable going somewhere because they understand where we're coming from.

Program 2’s director, ‘Lloyd,’ joined the program as its director eight years ago. He has embraced its culture and backed development of a faculty member-initiated pipeline program. He recruited Mike, an experienced African American PA educator known for his success supporting URM students, to focus solely on recruiting and mentoring URM and socioeconomically disadvantaged students interested in pursuing a PA career. When discussing the program’s new street medicine project, which he worked to establish, Lloyd relayed a story to illustrate the impact of class diversity.

Lloyd, Program 2 faculty interview: Our development of the street medicine program this year has tweaked our curriculum a little bit to start to prepare them for caring for those who experience homelessness. And having a couple of students in the room that experienced homelessness was a real shocker for the class and really humanized the issues… because they suddenly realized that their respective colleagues had that life experience.

Program practices

Admissions

Program 2 periodically makes changes to its admissions process but, unlike Program 1, has used a similar process for many years—long before the concept of holistic review gained recognition. Similar to Program 1’s admissions practices, Program 2’s practices are consistent with holistic review core principles. Mission-related factors, for example, comprise a substantial portion of the initial application screening matrix and interview scoring sheet. Additionally, individual candidate interviews are ‘blinded’ in that interviewers do not have access to candidates’ applications when evaluating them. Candidates are interviewed individually by a pair of program representatives comprised of a combination of faculty, adjunct faculty, or current students; and students and alumni conduct panels to answer candidate questions.

The admissions selection committee, which includes a subset of the faculty, is diverse, and like Program 1, Program 2 has a supplemental application questions about how the applicant will fulfill the program’s mission and about any instances of poor academic performance. Faculty, staff, and student interview data reinforce that the mission is central to selections decisions. One of the two admissions committee co-chairs, ‘Ben,’ a Latino faculty member, explained the approach he began using when he became co-chair: “…I’ll put the mission up on the screen. I'll say… ‘Let's read the mission. Let's just remember why we're here. Let's remember the type of student we want here.’ Right? That's all I would say.”

When asked about the most important applicant attributes, many faculty and staff identified ‘mission’ first, and all mentioned mission fit as a significant consideration. Like Program 1 faculty, they also mentioned the different perspectives that admissions selections committee members contribute. The faculty carefully attend to evaluating all applicants fairly, but considering different views appears to contribute a sense of equity and balance.

Outreach and recruitment

Program 2 faculty and students engage in numerous outreach activities focused on serving and engaging youth from diverse communities. Both faculty and students seemed inspired by the program’s commitment to a mission that welcomes disadvantaged students and students of color, fosters hiring diverse faculty and staff, and advocates for underserved communities. One student enthused, “…I knew they were true to their mission statement. And I saw their awards for diversity and I knew that they didn't only talk the talk but walk the walk.” Moreover, Lloyd (the program director) reported that promoting the program’s mission and diversity contribute to its success with URM enrollment.

Lloyd, Program 2 faculty interview: So, to me it's been really a mindfulness of trying to send a message to students of color, students from underrepresented minority backgrounds or disadvantaged communities that this is a welcome place and that also starts with hiring faculty and staff of underrepresented minority backgrounds and making sure that we have a reflective group of who we are as a culture.

Pipeline program activities, which include monthly sessions delivered to 60 youth from underserved areas, expose potential future students to various health professions and provide resources for support. ‘Nora,’ a Latina faculty member who in her youth participated in a health careers opportunity program (HCOP), spearheaded the program’s pipeline efforts when she joined the faculty approximately seven years ago. She noted that the pipeline program works because PA student volunteers lead the sessions, and a PA student volunteer stated that they keep coming back because the youth who participate are so inspiring.

Mike, whose work focuses on supporting undergraduate students specifically interested in the PA profession; Ben, the admissions committee co-chair; and Nora are all ‘champions for diversity’ identified at Program 2.

Academic support

Program 2 has formal and informal approaches to identifying and supporting struggling students. The formal process is based on assessing exam performance across courses, with one test failure triggering a meeting with the course directors, a second failure resulting in a learning contract stipulating use of different resources, and a third failure necessitating a meeting with and review by the student progress meeting, which “…looks at a broader depth and kind of kicks up the bar a little bit in terms of the level of support.”

In addition, course instructors work with students individually, and one faculty member has been designated to, among other responsibilities, provide learning support services. This faculty member noted that students who have never relied on others are often reluctant to ask for help. As part of her relatively new role, she hopes to establish a way to help students better prepare for the program’s challenging curriculum prior to starting classes. A few faculty members discussed ongoing efforts to provide more support, with one describing the program’s efforts as a continual “work in progress.”

Outcome measures

In addition to formally monitoring academic performance and student professionalism and informally assessing student body diversity, Program 2 faculty track what percentage of their students go on to practice in primary care and medically underserved areas. The program also surveys and interviews students as they exit the program to determine if certain program goals were achieved, including whether students developed a greater appreciation for diverse communities. At the time of the researcher’s program visit, faculty had just assessed for any associations between admissions criteria and attrition but found none. Regarding outcome measure impact on admissions, the program director noted that, in order to promote greater URM student enrollment, approximately five years ago, the program adjusted its initial application screening rubric to weight mission-related factors more heavily.

Cross-case analysis and discussion

In this section, we first discuss case differences, then address the research questions through an examination of case commonalities (see Table 4). Next, we describe factors other than program culture and practices that may influence URM enrollment and discuss study limitations and strengths.

Differences

As shown in Table 2, the programs differ with regard to several characteristics that have the potential to influence URM student attendance: admissions requirements, faculty demographics, and experience with holistic review (Alger & Carrasco, 1997; Coplan et al., 2018; Wells et al., 2011; Yuen & Honda, 2019). Although most PA schools require a standardized exam (e.g., 58% require the GRE and 6% accept the GRE or MCAT) and hands-on clinical experience for admission (Physician Assistant Education Association, 2020), Program 1 does not require a standardized exam. Program 2 does not require experience and is considering eliminating the standardized exam requirement. While limited, research suggests that the GRE is a poor predictor of PA certification exam performance and may be an obstacle for URM applicants, irrespective of score (Butina et al., 2017; Higgins et al., 2010; Yuen & Honda, 2019). In addition, the only study of prerequisite experience showed no relationship between hours of clinical experience prior to and clinical performance during PA school (Hegmann & Iverson, 2016). Whether clinical experience is a barrier for URMs has not been studied; however, Program 1 faculty determined that the types of experience they considered (prior to revising their admissions practices) were likely disadvantaging URMs. Overall, both programs have achieved high URM student enrollment (relative to other PA programs) despite different admissions requirements, which suggests that other influences may be more important.

Program 2’s more diverse faculty appears to attract URM students and clearly has a positive influence on the learning environment (Bowman, 2013; Umbach, 2006). Program 1’s faculty are more reflective of the overall PA population, which is approximately 80% non-Hispanic white (National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants, 2019); however, the staff and study body are diverse, which appears to positively impact program culture. In addition, Program 1 is recruiting more URM guest lecturers and recently hired its first African American faculty member. Thus, an appreciation for diverse representation among instructors appears to exist at both programs.

Program 1’s more recent transition to holistic admissions helps illuminate the fact that, although particular values may be necessary for effective holistic review, they may not be sufficient. Despite valuing diversity and inclusion, Program 1 did not achieve diverse student enrollment until the faculty deliberately aligned their admissions practices with those values. Additionally, while faculty and staff at both programs discussed the benefits of diversity among students, Program 1’s more recent experience with high proportions of URMs highlights the impact their perspectives can have on curriculum and culture. The story about the URM student asking to see people of color represented in course material is a strong example.

Commonalities and research questions

Central research question

How is diversity culture manifested in holistic review practices that achieve high URM student enrollment? Consistent with the conceptual model, authentic diversity culture at both programs appears to drive holistic admissions practices that have effectively achieved diverse student enrollment (see Table 4). Interestingly, neither program relied on established guidance when creating its admissions process. Instead, firmly held beliefs about the importance of serving underserved communities, which is an aspect of each program’s culture, served as a compelling motivator to develop practices that would promote URM attendance. Another important similarity is that both program leaders (i.e., program directors) seem to have translated beliefs about the value of diversity into actions that facilitate diversity-related goals, including asking individuals who we identified as champions for diversity to play leadership roles in the admissions process.

The influence of ‘champions’ may provide the greatest insight into how diversity culture manifests in admissions practices. In their eloquent study of Multiple Mini-Interview (MMI) interviewers’ ‘taste’—defined as “…individuals’ subjective judgments as a matter of practical sense”—Christensen and colleagues (2018, p. 292) describe the influence of alters (e.g., role models or leaders) on actors who, in the context of admissions, are applicant raters. They note that according to socialist Crossley (2013), “Alters teach actors how to appreciate and enjoy cultural objects that they might not otherwise ‘get’” (in Christensen et al., 2018, p. 291). Consequently, actors develop shared appreciation for alters’ tastes. (Christensen et al., 2018). Christensen et al. conclude that medical school applicant raters’ similar preferences for particular attributes may partially result from “shared habituated norms.” (Christensen et al., 2018, p. 301). They also note that enculturation appears to profoundly influence rater preferences for candidates who have attributes and characteristics with which they can identify.

By illuminating the influence that social interactions, habituated norms, and values may have on subjective rater judgments, it could be said that Christensen et al. (2018) demonstrated the influence of culture. Although we did not focus on how raters (i.e., faculty) form their impressions, it’s clear their judgments are influenced by program culture. At both programs, while different faculty perspectives are welcomed, having individuals (i.e., champions) who have deep insight into diverse communities participate in and help lead (or perhaps act as alters in) the admissions process facilitates a connection to those communities and appears to impart a stronger appreciation for applicant attributes associated with diversity-related program goals. Interestingly, the appreciation faculty seem to have for different points of view raises questions about the best way to achieve equity in admissions. For example, how do educational programs reconcile simultaneous recommendations to include diverse perspectives on admissions committees and strive for interrater reliability (Addams et al., 2010)?

Research sub-question 1

What specific admissions practices do programs that enroll high proportions of URM students use? Both programs’ admissions practices are consistent with recommendations for model holistic review (Addams et al., 2010; American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2016). Perhaps as a result of the insight gained from champions who understand the challenges that students from diverse backgrounds may face, both programs also include a question in their application that allows applicants to address instances of poor academic performance. In addition, current students are heavily involved in applicant interview experiences. Whether they influence URM attendance is unknown; however, based on URM student focus group data, current students of color in particular may help URM applicants feel comfortable and provide an indication that publicized commitments to diversity are authentic.

Research sub question 2

How are these practices supported? At both programs, outreach activities and engagement with a pipeline program contribute to working across a continuum of efforts aimed at supporting diverse student enrollment (Addams et al., 2010; Coleman et al., 2014; Glazer et al., 2018). Additionally, case study data suggest that involvement in pipeline programs, which students at both programs find rewarding, helps foster mentorship relationships. The proactive approach to academic support and faculty comments about the need to do more were also similar across programs, which suggests that supporting diverse classes of students requires sustained commitment. Finally, in response to monitoring diversity-related outcomes, both programs supported their holistic admissions practices by making revisions to promote greater diversity among students.

Potential alternative explanations for high URM enrollment

In a prior study, Hispanic/Latino and American Indian students described the pain of leaving home and feeling isolated when attending nursing school (Evans, 2004). Underrepresented minority students at both PA programs expressed a similar notion as they described choosing to apply to PA schools close to home or in diverse communities. Neither program was able to provide an accurate account of the percentage of their applicants that were URMs; however, both almost certainly receive more applications from URMs than programs located in areas with less diverse populations. Yet in 2010, Program 1, situated in an area with a diverse population, did not enroll any African American or Hispanic/Latino students. Therefore, while location may influence the ability to attract URM students, admissions and other program practices appear to have a stronger impact.

Another plausible explanation for high URM enrollment, not borne out by this study, is low tuition or the availability of scholarships. Tuition rates at both programs are higher than the average tuition for private programs and significantly higher than the average in-state tuition of $47,886 for public programs. Both programs have received U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration grants to provide scholarships for disadvantaged students, and Program 1 offers a need-based scholarship to two URM students in each cohort. However, scholarship award decisions are made after matriculation, and scholarship offerings do not reduce costs to an amount comparable to in-state tuition at public programs. Although tuition was identified as a “con” by URM students at both programs, it was not a deciding factor. Similarly, a national survey of PA students showed that they did not rate tuition and scholarships as very important or essential factors when selecting a PA program (Physician Assistant Education Association, 2018). Focus group data suggest that that URM students’ desire to be close to home and serve their communities counterbalanced their recognition of costs, which was mitigated by the potential for increased personal income and security.

Limitations and strengths

Limiting the study to two programs in the same geographic region was necessary to preserve the in-depth focus and integrity of the study methodology. However, because this case study was theory driven, the main concern was “… with the conditions under which the theory operates…,” not with ‘representativeness’ or statistical generalization of findings (Miles et al., 2014, p. 33). Thus, maximum variation sampling to promote transferability, and research questions and analysis driven by the conceptual model buttress the study, allowing for analytic generalization of the findings to the conceptual model (i.e., the theory) (Polit & Beck, 2010). Based on the findings, the model was supported and expanded (to include the potential impact of diverse classes of students on culture) in preparation for theoretical transfer to other ‘cases.’ We also promoted transferability of findings to PA and other health professions programs by offering propositions for further testing (which are described below) (Miles et al., 2014) and providing context-rich descriptions “… that allow readers to make inferences about extrapolating the findings to other settings” (Polit & Beck, 2010, p. 1453).

A possible bias of qualitative work is the potential for findings to be interpreted as more patterned than they actually are (Miles et al., 2014). We addressed this analytic bias by seeking negative evidence from study participants and investigating potential alternative explanations for high URM enrollment. In addition, several measures were undertaken to promote trustworthiness and authenticity (validity and reliability in quantitative terms). We strengthened confirmability by providing a detailed description of study procedures, analyzing data from multiple sources, and maintaining awareness of personal assumptions through the use of analytic memos. Finally, dependability and credibility were enhanced by using conceptually-driven analytic procedures replicated across cases, confirming findings with study participants, and triangulating across data sources (Miles et al., 2014).

Implications and conclusions

The benefits of interracial interactions among students include reduced prejudice and gains in psychological well-being, cognitive skills, and intellectual and civic engagement. (Bowman, 2013). Although we did not specifically assess the benefits of diversity, study findings shed further light on how students from diverse backgrounds may influence organizational culture. Consequently, the original conceptual model was revised to show that achieving diverse classes of students—which is a desired holistic review outcome—can reinforce or strengthen diversity culture. The connection is depicted as a dotted line, because the effect of failing to achieve high URM student enrollment is unclear.

Because factors known to facilitate effective holistic review were incorporated into the conceptual model, study findings, which supported the model, also help validate existing recommendations to advance holistic review: through outreach, by supporting students beyond the admissions process, and by monitoring diversity-related outcomes (Addams et al., 2010; American Association of Colleges of Nursing 2016; Association of American Medical Colleges n.d.; Glazer et al., 2016; Wros & Noone, 2018). Study findings also suggest that leader efforts to promote diversity can have a significant impact. Thus, prior insight about the need for leader buy-in (Glazer et al., 2016; Wros & Noone, 2018) was also supported. In addition, future examination of the specific influence of program-level leaders on holistic review may prove valuable.

By introducing a conceptual model for effective holistic review and illustrating the influence of diversity culture, this study may enhance health professions educators’ understanding of what successful holistic review involves. Additionally, the potentially meaningful new insights produced may serve as practical suggestions as well as propositions for further evaluation.

-

A commitment to service (e.g., in the community, through involvement in pipeline programs) may enhance diversity culture and strengthen efforts to enroll URM students.

-

Key informants or champions for diversity can significantly influence or shape the application evaluation process. Therefore, recruiting such individuals or having them assume a leadership role in admissions may increase the effectiveness of practices aimed at increasing URM enrollment.

-

Incorporating a question into the admissions application that provides applicants the opportunity to explain academic deficiencies may increase the racial and ethnic as well as socioeconomic diversity of those considered for and consequently offered admission to the program.

-

Programs committed to diversity can welcome and may attract URM candidates by incorporating diverse groups of students into the interview experience.

Marc Nivet (2012), former Association of American Medical Colleges Chief Diversity Officer, has observed that a huge disparity exists between declared commitments to diversity and demonstrable evidence of improvement. In relation to holistic review, going beyond mission statements and strategies by focusing on cultivating greater appreciation for diversity may help achieve more meaningful progress. Utilizing appropriate admissions practices is undeniably important; however, based on study findings, it is difficult to envision a circumstance where practices alone are highly effective.

While organizational culture may seem entrenched, change is possible. Moreover, the disproportionately high burden of COVID19 disease on minority populations along with worldwide protests sparked by racial injustice may serve as a catalyst for evaluating the impact of cultural attitudes and beliefs. Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM) purposefully created a new culture of compassion, respect, and collaboration through an innovative approach designed to prompt reflection on instances of desired attitudes and behaviors already being exhibited within the school (Cottingham et al., 2008). Notably, the culture change inspired several new initiatives, including revising the admissions process to promote matriculation of students whose attributes aligned with new cultural priorities (Cottingham et al., 2008). Considering the potential for change and the failure thus far to achieve widespread progress toward achieving a more diverse health workforce, it may be time to address diversity in admissions through a focus on culture.

References

Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant, Inc. (2018). Accreditation process. Retrieved June 5, 2020 from Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant. http://www.arc-pa.org/accreditation/standards-of-accreditation/.

Addams, A. N., Bletzinger, R. B., Sondheimer, H. M., White, S. E., & Johnson, L. M. (2010). Roadmap to diversity: Integrating holistic review practices into medical school admission processes. Association of American Medical Colleges.

Alger, J. R., & Carrasco, G. P. (1997, October 7). The role of faculty in achieving and retaining a diverse student population. American association of collegiate registrars and admissions officers policy summit, Denver, CO. Retrieved January 2, 2019 from the American Association of University Professors. https://www.aaup.org/issues/diversity-affirmative-action/resources-diversity-and-affirmative-action/role-faculty-achieving-and-retaining-diverse-student-population.

American Association of Colleges of Nursing (2016, July 12). Holistic review: A quick primer. Holistic admissions review in nursing. Retrieved March 1, 2019 from American Association of Colleges of Nursing. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Education-Resources/Tool-Kits/Holistic-Admissions-Tool-Kit.

Artinian, N. T., Drees, B. M., Glazer, G., Harris, K., Kaufman, L. S., Lopez, N., & Michaels, J. (2017). Holistic admissions in the health professions: Strategies for leaders. College and University: THe Journal of the American Association of Collegiate Registrars, 92(2), 65–68.

Association of American Medical Colleges (n.d.). Holistic review. Retrieved March 1, 2019 from Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/services/member-capacity-building/holistic-review.

Bowman, N. A. (2013). How much diversity is enough? The curvilinear relationship between college diversity interactions and first-year student outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 54(8), 874–894.

Butina, M., Wyant, A. R., Remer, R., & Cardom, R. (2017). Early predictors of students at risk of poor PANCE performance. Journal of Physician Assistant Education, 28(1), 45–48.

Christensen, M. K., Lykkegaard, E., Lund, O., & O’Neill, L. D. (2018). Qualitative analysis of MMI raters’ scorings of medical school candidates: A matter of taste? Advances in Health Sciences Education, 23(2), 289–310.

Cohen, J. J., Gabriel, B. A., & Terrell, C. (2002). The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Affairs, 21(5), 90–102.

Coleman, A. L., Lipper, K. E., Taylor, T. E., & Palmer, S. R. (2014). Roadmap to diversity and educational excellence: Key legal and educational policy foundations for medical schools (2nd ed., pp. 1–32). Association of American Medical Colleges.

Colorafi, K. J., & Evans, B. (2016). Qualitative descriptive methods in health science research. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 9(4), 16–25.

Coplan, B., Bautista, T. G., & Dehn, R. W. (2018). PA program characteristics and diversity in the profession. Journal of the American Academy of PAs, 31(3), 38–46.

Coplan, B., Todd, M., Stoehr, J., & Lamb, G. (2021). Holistic admissions and underrepresented minorities in physician assistant programs. Journal of Physician Assistant Education, 32(1), 10–19.

Cottingham, A. H., Suchman, A. L., Litzelman, D. K., Frankel, R. M., Mossbarger, D. L., Williamson, P. R., & Inui, T. S. (2008). Enhancing the informal curriculum of a medical school: A case study in organizational culture change. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(6), 715–722.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Sage.

Crossley, N. (2013). Interactions, juxtapositions, and tastes: Conceptualizing “relations” in relational sociology. In P. Christopher & D. François (Eds.), Conceptualizing relational sociology (pp. 123–143). Palgrave Macmillan.

Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A., & Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11(1), 100.

DeWitty, V. P. (2018). What is holistic admissions review, and why does it matter? Journal of Nursing Education, 57(4), 195–196.

Evans, B. C. (2004). Application of the caring curriculum to education of Hispanic/Latino and American Indian nursing students. Journal of Nursing Education, 43(5), 219–228.

Grabowski, C. J. (2018). Impact of holistic review on student interview pool diversity. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 23(3), 487–498.

Health Resources & Services Administration. (2019 July). Health workforce: Glossary. Retrieved September 1, 2019 from Health Resources & Services Administration. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/grants/resourcecenter/glossary.

Hegmann, T., & Iverson, K. (2016). Does previous healthcare experience increase success in physician assistant training? Journal of the American Academy of PAs, 29(6), 54–56.

Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. State Health Facts. Population distribution by race/ethnicity. (2016). Retrieved December 11, 2018 from Henry J. Kaiser Foundation. https://www.kff.org/state-category/demographics-and-the-economy/.

Higgins, R., Moser, S., Dereczyk, A., Canales, R., Stewart, G., Schierholtz, C., & Arbuckle, S. (2010). Admission variables as predictors of PANCE scores in physician assistant programs: A comparison study across universities. Journal of Physician Assistant Education Association, 21(1), 10–17.

Horsburgh, D. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12(2), 307–312.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

Institution of Education and Sciences. Integrated postsecondary education data system. (n.d.). Retrieved January 12, 2019 from National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/.

Felix, H., Laird, J., Ennulat, C., Donkers, K., Garrubba, C., Hawkins, S., & Hertweck, M. (2012). Holistic admissions process: An initiative to support diversity in medical education. Journal of Physician Assistant Education, 23(3), 21–27.

Glazer, G., Clark, A., Bankston, K., Danek, J., Fair, M., & Michaels, J. (2016). Holistic admissions in nursing: We can do this. Journal of Professional Nursing, 32(4), 306–313.

Glazer, G., Tobias, B., & Mentzel, T. (2018). Increasing healthcare workforce diversity: Urban universities as catalysts for change. Journal of Professional Nursing, 34(4), 239–244.

Lett, L. A., Murdock, H. M., Orji, W. U., Aysola, J., & Sebro, R. (2019). Trends in racial/ethnic representation among US medical students. JAMA Network Open, 2(9), e1910490–e1910490.

Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology:The APA publications and communications board task force report. American Psychologist, 73(1), 26–46.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Sage.

Mitchell, D. A., & Lassiter, S. L. (2006). Addressing health care disparities and increasing workforce diversity: The next step for the dental, medical, and public health professions. American Journal of Public Health, 96(12), 2093–2097.

Morgan, D. L. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research (Vol. 16). Sage.

Mulitalo, K. E., & Straker, H. (2007). Diversity in physician assistant education. Journal of Physician Assistant Education Association, 18(3), 46–51.

National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. (2019). 2018 Statistical profile of certified physician assistants. Retrieved September 1, 2019 from National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants https://www.nccpa.net/research.

Nivet, M. (2012). Commentary diversity and inclusion in the 21st century: Bridging the moral and excellence imperatives. Academic Medicine, 87(11), 1458–1460.

Owen, W. F., Carmona, R., & Pomeroy, C. (2020). Failing another national stress test on health disparities. Journal of the American Medication Association, 323(19), 1905–1906.

Physician Assistant Education Association. (2020). By the numbers: Program report 35: Data from the 2019 program survey. Retrieved January 24, 2021 from Physician Assistant Education Association. https://paeaonline.org/research/program-report/.

Physician Assistant Education Association. (2018). By the numbers: Student report 2: Data from the 2017 matriculating student and end of program surveys. Retrieved April 28, 2019 from Physician Assistant Education Association. https://paeaonline.org/research/program-report/.

Physician Assistant History Society. (2017). Timeline. Retrieved March 1, 2019 from Physician Assistant History Society. https://pahx.org/timeline/.

Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2010). Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: Myths and strategies. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(11), 1451–1458.

Proser, M., Bysshe, T., Weaver, D., & Yee, R. (2015). Community health centers at the crossroads: Growth and staffing needs. Journal of the American Academy of PAs, 28(4), 49–53.

Sandelowski, M. (1996). One is the liveliest number: The case orientation of qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 19(6), 525–529.

Sandelowski, M. (2011). “Casing” the research case study. Research in Nursing & Health, 34(2), 153–159.

Schein, E.H. & Schein, P. (2017). How to define culture in general. In: Organizational culture and leadership. (5th ed). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Schneider, B., Ehrhart, M. G., & Macey, W. H. (2013). Organizational climate and culture. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 361–388.

Scott-Findlay, S., & Estabrooks, C. A. (2006). Mapping the organizational culture research in nursing: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 56(5), 498–513.

Shin, P., Alvarez, C., Sharac, J., Rosenbaum, S. J., Vleet, A. V., Paradise, J., & Garfield, R. (2013, December 23). A profile of community health center patients: Implications for policy. Retrieved May 9, 2019 from Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/a-profile-of-community-health-center-patients-implications-for-policy/.

Slapar, F., Cook, B. J., Stewart, D., & Valachovic, R. W. (2018). Association report: U.S. dental school applicants and enrollees, 2017 entering class. Journal of Dental Education, 82(11), 1228–1238.

Stake, R. (2008). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Strategies of qualitative inquiry (Vol. 2, pp. 119–150). Sage.

Sullivan, L.W. (2004). Missing persons: Minorities in the health professions, a report of the sullivan commission on diversity in the healthcare workforce. Retrieved June 5, 2020 from https://drum.lib.umd.edu/handle/1903/22267.

Tierney, W. G. (2011). The impact of culture on organizational decision-making: Theory and practice in higher education. Stylus Publishing LLC.

Umbach, P. D. (2006). The contribution of faculty of color to undergraduate education. Research in Higher Education, 47(3), 317–345.

Urban Universities for HEALTH. (2014, September). Holistic admissions in the health professions: Findings from a national survey. Retrieved June 5, 2020 from https://urbanuniversitiesforhealth.org/media/documents/Holistic_Admissions_in_the_Health_Professions_final.pdf.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). Quick facts. Retrieved June 5, 2020 from U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045218.

U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019). Labor force statistics from the current population survey. Retrieved June 5, 2020 from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm.

Vick, A. D., Baugh, A., Lambert, J., Vanderbilt, A. A., Ingram, E., Garcia, R., & Baugh, R. F. (2018). Levers of change: A review of contemporary interventions to enhance diversity in medical schools in the USA. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 9, 53–61.

Wells, A., Brunson, W. D., Sinkford, J. C., & Valachovic, R. W. (2011). Working with dental school admissions committees to enroll a more diverse student body. Journal of Dental Education, 75(5), 685–695.

Witzburg, R. A., & Sondheimer, H. M. (2013). Holistic review: Shaping the medical profession one applicant at a time. New England Journal of Medicine, 368(17), 1565–1567.

Wros, P., & Noone, J. (2018). Holistic admissions in undergraduate nursing: One school’s journey and lessons learned. Journal of Professional Nursing, 34(3), 211–216.

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). Sage.

Yuen, C. X., & Honda, T. J. (2019). Predicting physician assistant program matriculation among diverse applicants: The influences of underrepresented minority status, age, and gender. Academic Medicine, 94(8), 1237–1243.

Zerwic, J. J., Scott, L. D., McCreary, L. L., & Corte, C. (2018). Programmatic evaluation of holistic admissions: The influence on students. Journal of Nursing Education, 57(7), 416–421.