ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Recent data suggest that aspirin may be effective for reducing cancer mortality.

OBJECTIVE

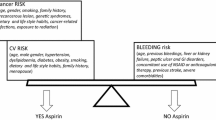

To examine whether including a cancer mortality-reducing effect influences which men would benefit from aspirin for primary prevention.

DESIGN

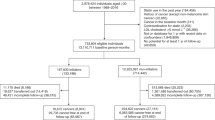

We modified our existing Markov model that examines the effects of aspirin among middle-aged men with no previous history of cardiovascular disease or diabetes. For our base case scenario of 45-year-old men, we examined costs and life-years for men taking aspirin for 10 years compared with men who were not taking aspirin over those 10 years; after 10 years, we equalized treatment and followed the cohort until death. We compared our results depending on whether or not we included a 22 % relative reduction in cancer mortality, based on a recent meta-analysis. We discounted costs and benefits at 3 % and employed a third party payer perspective.

MAIN MEASURE

Cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained.

KEY RESULTS

When no effect on cancer mortality was included, aspirin had a cost per QALY gained of $22,492 at 5 % 10-year coronary heart disease (CHD) risk; at 2.5 % risk or below, no treatment was favored. When we included a reduction in cancer mortality, aspirin became cost-effective for men at 2.5 % risk as well (cost per QALY, $43,342). Results were somewhat sensitive to utility of taking aspirin daily; risk of death after myocardial infarction; and effects of aspirin on stroke, myocardial infarction, and sudden death. However, aspirin remained cost-saving or cost-effective (< $50,000 per QALY) in probabilistic analyses (59 % with no cancer effect included; 96 % with cancer effect) for men at 5 % risk.

CONCLUSIONS

Including an effect of aspirin on cancer mortality influences the threshold for prescribing aspirin for primary prevention in men. If such an effect is real, many middle-aged men at low cardiovascular risk would become candidates for regular aspirin use.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1849–60.

Berger JS, Roncaglioni MC, Avanzini F, Pangrazzi I, Tognoni G, Brown DL. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events in women and men: asex-specific meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006;295(3):306–13. Erratum in: JAMA. 2006 May 3;295(17):2002. PubMed PMID:16418466.

Hernandez-Diaz S, Garcia Rodriquez LA. Cardioprotective aspirin users and their excess risk of upper gastrointestinal complications. BMC Med. 2006;4:22.

De Berardis G, Lucisano G, D’Ettorre A, et al. Association of aspirin use with major bleeding in patients with and without diabetes. JAMA. 2012;307(21):2286–94.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(6):396–404.

Berger JS, Lala A, Krantz MJ, Baker GS, Hiatt WR. Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular events in patients without clinical cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am Heart J. 2011;162(1):115–24.e2. Review. PubMed PMID: 21742097.

Raju N, Sobieraj-Teague M, Hirsh J, O’Donnell M, Eikelboom J. Effect of aspirin on mortality in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Am J Med. 2011;124(7):621–9. Epub 2011 May 17. PubMed PMID: 21592450.

Sanmuganathan PS, Ghahramani P, Jackson PR, Wallis EJ, Ramsay LE. Aspirin for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: safety and absolute benefit related to coronary risk derived from meta-analysis of randomised trials. Heart. 2001;85(3):265–271.

Seshasai SR, Wijesuriya S, Sivakumaran R, et al. Effect of aspirin on vascular and nonvascular outcomes: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(3):209–16. Epub 2012 Jan 9. Review. PubMed PMID: 22231610.

Pignone M, Earnshaw S, Tice JA, Pletcher MJ. Aspirin, statins, or both drugs for the primary prevention of coronary heart disease events in men: a cost-utility analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(5):326–36.

Earnshaw SR, Scheiman J, Fendrick AM, McDade C, Pignone M. Cost-utility of aspirin and proton pump inhibitors for primary prevention. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(3):218–25. PubMed PMID: 21325111; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3137269.

Greving JP, Buskens E, Koffijberg H, Algra A. Cost-effectiveness of aspirin treatment in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease events in subgroups based on age, gender, and varying cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2008;117(22):2875–83. Epub 2008 May 27. PubMed PMID: 18506010.

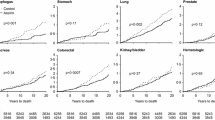

Rothwell PM, Fowkes FG, Belch JF, Ogawa H, Warlow CP, Meade TW. Effect of daily aspirin on long-term risk of death due to cancer: analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;377(9759):31–41. Epub 2010 Dec 6. PubMed PMID: 21144578.

Chan AT, Cook NR. Are we ready to recommend aspirin for cancer prevention? Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1569–71. Epub 2012 Mar 21. PubMed PMID: 22440945.

Pignone M, Earnshaw S, Pletcher MJ, Tice JA. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women: a cost-utility analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(3):290–5.

Lampe FC, Whincup PH, Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Walker M, Ebrahim S. The natural history of prevalent ischaemic heart disease in middleaged men. Eur Heart J. 2000;21(131):1052–62.

Dennis MS, Burn JP, Sandercock PA, Bamford JM, Wade DT, Warlow CP. Long term survival after first-ever stroke: the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project. Stroke. 1993;24(6):796–800.

Anderson KM, Odell PM, Wilson PWF, Kannel WB. Cardiovascular disease risk profiles. Am Heart J. 1991;121(part 2):293–8.

Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu JQ, Murphy SL. Deaths: Final Data for 2005. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 56 no 10. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008.

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. SEER*Stat Database: Mortality - All COD, Aggregated With State, Total U.S. (1969-2007), National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch, released April 2009. Available at: www.seer.cancer.gov. Accessed on September 8, 2011.

van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EA, et al. Acute upper GI bleeding: did anything change? Time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(7):1494–9.

Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom: Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. BMJ. 1995;311:222–226.

Rothwell PM, Price JF, Fowkes FG, et al. Short-term effects of daily aspirin on cancer incidence, mortality, and non-vascular death: analysis of the time course of risks and benefits in 51 randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1602–12. Epub 2012 Mar 21. Review. PubMed PMID: 22440946.

He J, Whelton PK, Vu B, Klag MJ. Aspirin and risk of hemorrhagic stroke. JAMA. 1998;280(22):1930–5.

LaRosa JC, He J, Vupputuri S. Effect of statins on risk of coronary disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1999;282(24):2340–6.

Meara E, White C, Cutler DM. Trends in medical spending by age, 1963-2000. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;23(4):176–183.

Lubitz J, Cai L, Kramarow E, Lentzner H. Health, life expectancy, and health care spending among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(11):1048–1055.

U.S. Department of Labor, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, US city average, not seasonally adjusted medical care. http://data.bls.gov/PDQ/outside.jsp?survey=cu. Accessed February 2012.

Naderi SH, Bestwick JP, Wald DS. Adherence to drugs that prevent cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis on 376,162 Patients. Am J Med. 2012 Jun 27.[Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 22748400.

Hayden M, Pignone M, Phillips C, Mulrow C. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a summary of the evidence for the US preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(2):61–172.

Straube S, Tramèr MR, Moore RA, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Mortality with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation: effects of time and NSAID use. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:41.

www.Walgreens.com, accessed 9Sep11.

Ingenix, Inc. The Essential RBRVS (2012): A comprehensive listing of RBRVS values for CPT and HCPCS Codes. St. Anthony Publishing, 2012.

HCUPnet. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.ahrq.gov/HCUPnet/ Accessed 7Mar2012.

Friedman B, La Mare J, Andrews R, McKenzie DH. Assuming an average cost to charge ratio of 0.5: practical options for estimating cost of hospital inpatient stays. J Health Care Finance. 2002;29(1):1–13.

Russell MW, Huse DM, Drowns S, Hamel EC, Hartz SC. Direct medical costs of coronary artery disease in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81(9):1110–5.

Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics - 2011 Update: A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2011;123(4):e18–e209.

Leibson CL, Hu T, Brown RD, Hass SL, O’Fallon WM, Whisnant JP. Utilization of acute care services in the year before and after first stroke: A population-based study. Neurology. 1996;46(3):1–13.

Menzin J, Wygant G, Hauch O, Jackel J, Friedman M. One-year costs of ischemic heart disease among patients with acute coronary syndromes: findings from a multi-employer claims database. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(2):461–468.

Augustovski FA, Cantor SB, Thach CT, Spann SJ. Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(12):824–35.

Nease RF, Kneeland T, O’Connor GT, et al. Variation in patient utilities for outcomes of the management of chronic stable angina. JAMA. 1995;273(5):1185–90.

Gore JM, Granger CB, Simoons ML, Sloan MA, Weaver WD, White HD, et al. Stroke after thrombolysis: mortaltiy and functional outcomes in the GUSTO-I trial. Circulation. 1995;92(10):2811–8.

Tsevat J, Goldman L, Soukup JR, et al. Stability of time-tradeoff utilities in survivors of myocardial infarction. Med Decis Making. 1993;13(2):161–5.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Brenda Denzler and Penny Chumley for their assistance with editing and manuscript formatting.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by Partnership for Prevention and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R21 HL112256-01). Dr. Pignone was also supported through an Established Investigator Award from the National Cancer Institute (K05CA129166). Funders had no role in the design of the study, conduct of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, or preparation and approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Earnshaw and Ms. McDade are employees of RTI Health Solutions, a contract research company that receives funds from pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and medical device/diagnostic manufacturers to perform outcomes research for cardiovascular disease and other conditions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 231 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pignone, M., Earnshaw, S., McDade, C. et al. Effect of Including Cancer Mortality on the Cost-Effectiveness of Aspirin for Primary Prevention in Men. J GEN INTERN MED 28, 1483–1491 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2465-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2465-6