Abstract

Background

Successful implementation of new care models within a health system is likely dependent on contextual factors at the individual sites of care.

Objective

To identify practice setting components contributing to uptake of new team-based care models.

Design

Convergent mixed-methods design.

Participants

Employees and patients of primary care practices implementing two team-based models in a large, integrated health system.

Main measures

Field observations of 9 practices and 75 interviews, provider and staff surveys to assess adaptive reserve and burnout, analysis of quality metrics, and patient panel comorbidity scores. The data were collected simultaneously, then merged, thematically analyzed, and interpreted by a multidisciplinary team.

Key results

Based on analysis of observations and interviews, the 9 practices were categorized into 3 groups—high, partial, and low uptake of new team-based models. Uptake was related to (1) practices’ responsiveness to change and (2) flexible workflow as related to team roles. Strength of local leadership and stable staffing mediated practices’ ability to achieve high performance in these two domains. Higher performance on several quality metrics was associated with high uptake practices compared to the lower uptake groups. Mean Adaptive Reserve Measure and Maslach Burnout Inventory scores did not differ significantly between higher and lower uptake practices.

Conclusion

Uptake of new team-based care delivery models is related to practices’ ability to respond to change and to adapt team roles in workflow, influenced by both local leadership and stable staffing. Better performance on quality metrics may identify high uptake practices. Our findings can inform expectations for operational and policy leaders seeking to implement change in primary care practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Team-based care models are broadly recognized as important to primary care reform efforts.1,2,3,4,5,6 While new models of care delivery may be associated with changes in quality of care as well as patient and provider experience,7, 8 the transition to team-based care is complicated.9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 Understanding local contextual factors influencing application of team-based models in primary care is likely to be important to their implementation. The ability to successfully respond to practice change, or capacity for change, measured as practice adaptive reserve, is often based upon relationships—both among team members and between team members and patients.18,19,20 Team characteristics such as work experience may affect a practice’s capacity for change,13, 21, 22 can be associated with team staffing or turnover,23 and can further influence the success of model implementation.

The Cleveland Clinic Health System (CCHS), a large, integrated health system, in 2013–2014 implemented team-based models redefining roles for medical assistants (MAs) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) for groups of physicians at diverse practice sites (urban, rural, and suburban). Usual care at these sites included one medical assistant assigned to each physician for a clinic session. In “team-care (TC),” two MAs or LPNs assigned to one physician performed team documentation (scribing) and administrative work. In a second model, or “modified team-care (MTC),” an additional MA assigned to a group of three physicians (for a total of 4 MAs per team) helped with clinical workflow or administrative work. Each practice site had at least one assigned nurse care coordinator (NCC) focused on outreach to medically complex patients. Physicians participated voluntarily in these new models which improved access by offering an additional three patient slots per half day per physician in TC or per group of three physicians in the MTC model. In 2016, there were 14 physicians at 7 sites participating in TC and 8 physicians at 3 sites in the MTC model. Our goal was to identify characteristics in the practice settings that contributed to uptake of these new models.

METHODS

We performed a comparative case study of nine primary care practices where physicians implemented either (or both) of these models using a convergent mixed methods approach24 (Fig. 1). Qualitative data collection included field observations and interviews. Quantitative data collection included survey administration, analysis of quality metrics, and patient panel comorbidity scores. Data were collected simultaneously then merged and interpreted.

Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

Physician leaders at each practice were informed about the study through presentations and electronic communication. Field observations and informal interviews were conducted by a physician-researcher (AMH) and a research nurse (JF) over 4 h at practices with at least one physician and team practicing in a new model. Field notes were recorded independently using an iteratively created observation template. Follow-up observations were conducted at seven of the nine sites based on provider agreement.

To understand practice characteristics that may be unrelated to the practice model, employees and patients of providers practicing in the new models as well as usual care were invited to participate in informal and formal interviews. Separate interview guides for employees and patients were created, with questions about primary care experiences, perception of practice changes, unique practice characteristics, relationships, and thoughts about the future of primary care. All interview participants gave verbal consent. Patients were offered a $10 gift card for formal interview participation, with no incentive offered to employees. We interviewed physicians, at least one of their team MAs or LPNs, NCC, and a convenience sample of patients with up to two patients per team. The formal interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed.

Field notes and informal interviews were coded by AMH and reviewed by JF and MBM. Formal interview transcripts were coded and analyzed by AMH and MBM. Themes from field notes and interviews were derived by AMH using an editing style qualitative analysis,25, 26 with themes identified as they emerged from the data, reviewed by MBM and discussed. The discoveries from the field observations and interviews were then organized using a framework method of analysis.27 Validation included (1) initial findings presented to members of a primary care stakeholder panel comprised of patients and primary care employees (physicians, research nurse, nurse care coordinator, medical assistants, quality administrator, program manager) and (2) thematic results audited by researchers not directly involved in the line-by-line coding (AP, DA and KS). Qualitative analyses were performed using NVivo software, version 11.28

Quantitative Data Collection and Analysis

To understand practice staff adaptive reserve and burnout, we created a survey including a three-item Adaptive Reserve Measure20 and the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI).29 The survey was distributed electronically using REDCap30 in November–December 2016 (Time 0), then at a 6-month follow-up in June 2017 (Time 1) to 813 (Time 0) and 738 (Time 1) outpatient primary care employees including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, MAs, LPNs, nurses, and administrative staff at all 37 sites in the CCHS. Three reminders followed each initial request. Mean Adaptive Reserve scores and MBI scores for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment were calculated.

Routinely collected data on provider performance on Accountable Care Organization (ACO) Quality Measures31 was obtained, reported as percentage of a provider’s eligible patients meeting criteria for the measure. Preventive care measures for influenza and pneumococcal vaccination, colorectal cancer screening, and mammography were obtained. Chronic disease measures were obtained for diabetes control (glycosylated hemoglobin (Hba1c) < 8%) and hypertension control (blood pressure < 140/90). Mean scores for each measure were calculated for providers at each site for 2016 then tabulated as mean rate of compliance for each measure by site. To assess variation in patient disease severity at each site, patient panel comorbidity was estimated by Charlson scores32 and reported as a mean for the group of providers by site.

We used means, standard deviations and percentiles to describe continuous measures, and frequencies and percentiles to summarize categorical measures. The Pearson’s chi-square tests, Fisher’s exact tests, Cochran-Armitage trend tests, or Mantel-Haenszel chi-square tests were used to assess associations between categorical factors. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) models were performed to evaluate the relationship between the continuous outcomes and categorical group variables. Variable significance was tested using Tukey/Bonferroni to adjust for multiple comparisons. All tests were performed at a significance level of 0.05. SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R 3.4 software were used for analyses. The quantitative comparisons had a power of 80% to detect effect size of 2.2 in mean scores of adaptive reserve between the groups of practices.

Mixed Methods Analysis

Practices were classified into groups based upon qualitative analyses. In the merged analysis, the quantitative data was then compared across the practices and practice groupings. General linear mixed effects models were created to assess the association between the summarized measures and group, where the correlation within the same site was taken into consideration. This protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Cleveland Clinic.

RESULTS

Our analyses (1) classify practices based on their degree of uptake of the team-based care model, (2) describe themes influencing care model uptake and depict their relationship, and (3) present quantitative analyses that provide context for interpreting these qualitative findings.

Qualitative Field Observations and Interviews

In total, we conducted practice observations and informal interviews at 9 sites, follow-up observations at 7 sites, and 75 in-depth interviews including 19 physicians (13 practicing in team-based models, 5 in usual care at the same sites, 1 was a key informant), 18 MAs/LPNs, 8 NCC, and 30 patients.

Three themes initially emerged from field observations and informal interviews: flexible roles/practice modifications, practice challenges, and relationships, with subsequent open coding of the 75 in-depth interviews yielding 5 major themes that encompassed the initial themes: practice characteristics related to response to change, flexible workflow as related to team roles, relationships, practice challenges, and future of primary care.

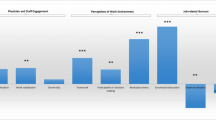

Variability in Observed Uptake to Team-Based Models and Practice Site Groupings

A key finding that was apparent from the initial field observations was the variability in uptake of the new team-based models as originally intended. Sites were eventually classified into groups based upon the level of uptake of the new models. The level of uptake was discerned from our extensive data analysis that included (1) our initial observations of fidelity to the originally proposed model, (2) our informal interviews during the observation phase, and (3) our formal interviews. As we synthesized our data and the themes emerged through analysis, we concluded that the observed fidelity was defined by differences in two of the five emergent themes: practice characteristics related to response to change and flexible workflow as related to team roles. From observed differences in these two themes, the following three group classification structures for the practices emerged: group 1: high uptake = sites 1, 3, 4, and 6; group 2: partial uptake = sites 5, 8, and 9; and group 3: lower uptake = sites 2 and 7. High vs. low responsiveness to change and high vs. low flexibility related to team roles differentiated high vs. low uptake practices. During further qualitative analysis, the strength of local leadership and stable staffing emerged as mediators to these two themes in their effects on model uptake. Low uptake practices lacked both strong local leadership and stable staffing; the partial uptake practices lacked either strong leadership or stable staffing whereas high uptake practices had both (Fig. 2). Example quotes supporting the two major differentiator themes are described below.

Practice Characteristics as Related to Response to Change

Group 1—high uptake

Group 1, observed to have the highest uptake and to maintain the greatest fidelity to the initial implementation of TC or MTC, was highly responsive to change. As a physician in group 1 (practice site 1) commented,

“… the way I see it, you’ve got to be on the move…things are rapidly evolving in … healthcare and you’ve got to remain nimble.”

A NCC at practice site 6 stated,

“So change, in my opinion, is very good. I think it shows growth. It shows an investment in the area”

and a patient (practice site 6) noted,

“So everything is constantly, it’s changing in a good way.”

The role of leadership in supporting change was highlighted by a physician in this group (practice site 3):

“I think we’ve had a lot of advantages in just the attitude and personality of our people, and certainly the tone has been set by our leadership of ‘Hey. Let’s figure this out, instead of having somebody else tell us how to do it.”

This data suggests that viewing change positively and support from leadership could contribute to maintaining high uptake of new models. In addition, stability of team MA staffing was observed in this group, with a consistent number of available staff to participate in the team-based models.

Group 2—partial uptake

Group 2 practices were observed to respond to change through adapting the implementation of the models to meet their needs. This included varying the roles of MAs/LPNs, especially related to the amount of time they spent in the patient exam room as scribes (often based upon patient’s presenting complaint) vs. administrative work. As one LPN (practice site 9) commented, highlighting the ability to adapt the original team-based model,

“I think as a whole, our group of individuals do pretty well with change and adapt as we go along.”

Physicians adapted their own workflow including scheduling and documentation to utilize the available MAs/LPNs efficiently. At one site, two of the physicians prepared ahead of time for the MA scribe visit documentation to maximize face time with patients. In this group, unstable staffing, such as provider or MA turnover or call-offs, presented challenges and required adaptation of the model. Of note, in two of the practices, teams discontinued participation in a team-based model because of staffing issues. Again, however, the importance of needing the support of leadership in adapting to change was highlighted by a NCC (practice site 8):

“I think we will see a lot of positive come out of this, working together… I think we will have some pushback, and I think we’re gonna need support from leadership to really help this be successful.”

These qualitative findings suggest the importance of leadership support, stable staffing, and positive view of adapting to change to maintain model uptake.

Group 3—lower uptake

For the group 3 sites, staffing changes were a major barrier to adoption of the new models as initially implemented. For example, at one of these sites, implementation ceased for almost a full year because of MA staffing and other providers stopped practicing in a team-based model prior to the start of the study. The other site experienced significant physician turnover. However, lower interest in responding to changes may have also played a role, as one physician commented (practice site 2),

“I’m too old-fashioned…don’t want MA in the room typing.”

Flexible workflow as related to team roles

Group 1—high uptake

Practices successful in model implementation demonstrated willingness among team members to adapt to new roles. For example, an MA in group 1 (practice site 6) stated:

“…I basically do everything. I work with the doctors. I’ll room patients and we’ll do the backup for the patients. I also help on phones… I also do front desk…”

Group 2—partial uptake

A physician in group 2 (practice site 8) highlighted the need for changing team roles, in this case for the MA, based upon a patient’s presenting symptom, where the choice may be to limit the role of the MA in certain situations:

“The MAs, they’ve been trained to review Family Medical History, Past Medical Histories. They’re supposed to review the Medication List, Smoking History… and then they can take a brief, subjective exam…It works well if it is only a known diagnosis… but if a patient comes in with a problem, that doesn’t work as well.”

Group 3—lower uptake

In contrast, more rigid MA roles, and less flexibility, were observed in group 3 practices. For example, in practice site 2, one MA was described as spending 75% of her time on paperwork for the providers, and 25% on covering staffing needs.

However, team support was still noted in this group, as a physician (practice site 7) noted:

“I could say some of the stuff I’m doing was what a Social Worker should be doing, and now we seem we have much more support in terms of doing that.”

Appendix Table 1 presents further examples supporting the axis of differentiating thematic results.

Three additional themes were similar across all of the practices in the study including relationships, practice challenges, and thoughts on the future of primary care. Team members valued relationships, both among team members and with patients, as a physician in group 1 stated, “part of the reason you went into primary care is the relationships.” Perceptions of practice challenges were similar and included pressures for external reporting taking away from face time with patients, interruptions, and competing demands in clinic and staffing challenges. Additional appointment slots, particularly when the added patients were not known to the physician, after visit work, care delivery for complex patients including cost, transportation, and access to specialists were challenges. As noted by an employee in group 2, “so maybe our primary care clinicians have to do more things that they used to maybe refer to specialty.” Perceptions of the future of primary care included hope for more team-based care delivery, improved care for patients, and concern about meeting the demands of day-to-day practice to deliver high-quality care. As a physician in group 1 mentioned, “I think we’re starting to recognize the value in Primary Care in delivering higher quality care at lower cost…”

Additional illustrations of these three themes are presented in Appendix Table 2.

Patient Perceptions

Patient opinions were similar across sites. Patients were satisfied with their care, either did not notice significant changes in care delivery or frequently felt the changes were positive. Even in lower uptake practices, the changes in team roles were viewed positively by patients, as noted in the following exchange at practice site 7:

Interviewer: “Do you like that there are two workers in the room at one time? Does that bother you, or would you rather be with the physician alone?”

Patient: “No. It doesn’t, because it’s some things he needs, so she’s right there… The team is where she’s working with him, and sometimes she’s on the computer and sometimes she’s not, but he might need a question answered, and she got the answer for him.”

Patients valued shorter wait times, time and relationship with their physician, and involvement of other team members. They noted issues of health care cost and role of insurance. Thoughts on the future of primary care were related to convenience as well as maintaining the physician-patient relationship.

Stakeholder Panel Input

Insights from the initial field observations and interviews were confirmed with the stakeholder panel at meetings in October 2016 and April 2017. Many patient members had not noted significant changes in care delivery, valued time spent with the physician, and smooth workflow procedures and reported an overall acceptance of team-based care.

Survey

After excluding employee respondents who reported not working in primary care, there were 276 respondents (response rate 35%) at time 0 and 238 at time 1 (response rate 33%). Characteristics of survey respondents are shown in Table 1 at time 0 and time 1.

There was no significant difference in results of the mean adaptive reserve scores and mean MBI scores for the nine qualitative observation sites and no significant differences in patient panel comorbidity scores among the nine sites (Appendix Table 3). Results of linear mixed effects models of Adaptive Reserve and MBI scores both at time 0 and time 1 by uptake group are displayed in Table 2. There were no significant differences between high, partial, or low uptake practices in Adaptive Reserve estimates at either time point except for slightly higher MBI emotional exhaustion estimates at time 1 compared to time 0 in the low uptake group 3 compared to the partial uptake group 2. Across practices, no significant differences in MBI scores were noted between physicians or MAs and LPNs who worked in a scribe model compared to those who did not either in time 0 or time 1 (Appendix Table 4).

Quality Scores

The ACO metrics for influenza and pneumococcal vaccination, colorectal cancer screening, and mammography were higher for group 1 practices compared to groups 2 or 3 (Table 3). The percentage of patients who had controlled diabetes was higher in group 1 compared to groups 2 and 3 while control of hypertension was not better in group 1. For the hypertension metric, group 2 scored best while performance for groups 1 and 3 were similar (Table 3).

Mixed Methods Interpretation

A visual display of qualitative and quantitative results is presented in Table 4 summarizing the relative performance on the two differentiating qualitative themes and quality metrics by model uptake grouping.

DISCUSSION

In this mixed methods analysis, we identified an emergent classification structure of primary care practices defined by level of uptake of team-based models. The importance of practice characteristics related to response to change and ability to adapt workflow/team roles were key themes that captured the successful uptake of new models. Local leadership and stable staffing were essential components of mediating model uptake. Support from leadership was perceived as important to sustaining acceptance to the change in practice models and promoted an attitude of responsiveness to change. Lack of stable staffing often contributed to the need for physicians to opt out of the new models and did not allow for flexibility of work roles. Practice characteristics reflected the practice site and not the care delivery model, as similar observation and interview themes were noted across the TC, MTC, and usual care models. Perceptions of the value of relationships, practice challenges, and the future of primary care appeared to reflect the current state of primary care practice overall, and were not related to degree of uptake of the models.

Cohen et al. identified four key elements in a model for practice change in primary care including (1) motivation of key stakeholders, (2) resources for change, (3) outside motivators, and (4) opportunities for change.33 In our work, strong local leadership served as motivated key stakeholders, and stable staffing was a resource for change, with both of these influencing responsiveness to change, and allowing for flexible team roles. Outside motivators, specifically the need for improved practice efficiency, and opportunities to change, were similar across sites.

The level of model uptake was not explained by practices’ adaptive reserve, provider burnout, and patient comorbidities. The slight increase in emotional exhaustion scores in the low uptake group on the 6-month survey suggests the need for further exploration of whether factors that prevent model uptake may also contribute to provider burnout. Interestingly, MBI scores were overall moderate to high for personal accomplishment, suggesting internal motivation to succeed in all practice groupings. Quality scores were also similar among the sites. These quantitative results suggest generally well-functioning practices providing quality care.

However, performance on preventive care and diabetes disease control measures was stronger in practices where team-based model uptake was observed to be the highest. This suggests that perhaps the same qualities required to maintain new models of care are required to deliver higher-quality clinical care. While the high-uptake group did not perform better on the hypertension metric, the partial uptake group did perform well. The ability to successfully make modifications in each setting may also help with model success.34

The importance of studying context in evaluating success of implementation efforts is now well-recognized.35,36,37 Our finding of individual practice characteristics and response to change as well as flexibility with workflow and team roles as the important factors in successful implementation of team based-primary care is consistent with previous findings,9 and the association of team-based primary care with quality of care has also been described.38

While our study was limited to one health system, the diversity of practice sites included may allow our findings to be further generalizable. Where practice efficiency is the primary goal, operational leaders should consider assessment of practices as to the presence and engagement of local leadership, understanding that stable staffing that can adapt team roles, and the ability to respond to change are of paramount importance in implementing new care delivery models. Quality metrics may also be used to identify practices with characteristics that predispose certain teams to high uptake of new models. Such practices may make ideal test sites.

CONCLUSION

Uptake of team-based models at the practice level can be powerfully influenced by a practice’s ability to respond to change and to adapt workflow and team roles, affected by local leadership and stable staffing. Practices with high uptake of new models also performed better overall on quality metrics. Our findings can inform expectations for operational and policy leaders seeking to implement change in primary care practices.

References

Mitchell et al. Core Principles & Values of Effective Team-Based H.pdf. https://www.nationalahec.org/pdfs/vsrt-team-based-care-principles-values.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2018.

Green LV, Savin S, Lu Y. Primary Care Physician Shortages Could Be Eliminated Through Use Of Teams, Nonphysicians, And Electronic Communication. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(1):11–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1086

Home|PCMH Resource Center. https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/. Accessed July 5, 2018.

Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) - Patient Care Services. https://www.patientcare.va.gov/primarycare/PACT.asp. Accessed July 5, 2018.

Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. https://www.aap.org/en-us/professional-resources/quality-improvement/Pages/Joint-Principles-of-the-Patient-Centered-Medical-Home.aspx. Accessed July 5, 2018.

The Patient-Centered Medical Home’s Impact on Cost and Quality: Annual Review of Evidence, 2014–2015 | Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. https://www.pcpcc.org/resource/patient-centered-medical-homes-impact-cost-and-quality-2014-2015. Accessed July 5, 2018.

Nelson KM, Helfrich C, Sun H, et al. Implementation of the patient-centered medical home in the veterans health administration: Associations with patient satisfaction, quality of care, staff burnout, and hospital and emergency department use. JAMA Intern Med. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2488

Sylling PW, Wong ES, Liu C-F, et al. Patient-Centered Medical Home Implementation and Primary Care Provider Turnover. Med Care. 2014:1. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000230

Wagner EH, Flinter M, Hsu C, et al. Effective team-based primary care: observations from innovative practices. BMC Fam Pract 2017;18(1):13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-017-0590-8

Stock R, Mahoney E, Carney PA. Measuring team development in clinical care settings. Fam Med 2013;45(10):691–700.

Cronholm PF, Shea JA, Werner RM, et al. The patient centered medical home: mental models and practice culture driving the transformation process. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28(9):1195–1201. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2415-3

Calman NS, Hauser D, Weiss L, et al. Becoming a patient-centered medical home: a 9-year transition for a network of Federally Qualified Health Centers. Ann Fam Med 2013;11 Suppl 1:S68–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1547

Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Stange KC, Stewart E, Jaén C. Transforming physician practices to patient-centered medical homes: lessons from the national demonstration project. Health Aff Proj Hope 2011;30(3):439–445. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0159

Eubank D, Orzano J, Geffken D, Ricci R. Teaching team membership to family medicine residents: what does it take? Fam Syst Health J Collab Fam Healthc 2011;29(1):29–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022306

Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL, et al. Primary care practice transformation is hard work: insights from a 15-year developmental program of research. Med Care 2011;49 Suppl:S28–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181cad65c

Landon BE, Gill JM, Antonelli RC, Rich EC. Using evidence to inform policy: developing a policy-relevant research agenda for the patient-centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25(6):581–583. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1303-3

Chesluk BJ, Holmboe ES. How teams work--or don’t--in primary care: a field study on internal medicine practices. Health Aff Proj Hope 2010;29(5):874–879. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1093

Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Stange KC, Jaen CR. Primary Care Practice Development: A Relationship-Centered Approach. Ann Fam Med 2010;8(Suppl 1):S68-S79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1089

Jaen CR, Crabtree BF, Palmer RF, et al. Methods for Evaluating Practice Change Toward a Patient-Centered Medical Home. Ann Fam Med 2010;8(Suppl 1):S9-S20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1108

Shorter Adaptive Reserve Measures. Annals of Family Medicine Vol 10, No 3 Online Supplementary Data. http://www.annfammed.org/content/suppl/2012/04/13/8.Suppl_1.S9.DC2/Shorter_Adaptive_Reserve_Measures.pdf. Published June 2012.

Gabbay RA, Friedberg MW, Miller-Day M, Cronholm PF, Adelman A, Schneider EC. A Positive Deviance Approach to Understanding Key Features to Improving Diabetes Care in the Medical Home. Ann Fam Med 2013;11(Suppl 1):S99-S107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1473

Bobiak SN, Zyzanski SJ, Ruhe MC, et al. Measuring practice capacity for change: a tool for guiding quality improvement in primary care settings. Qual Manag Health Care 2009;18(4):278–284. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/QMH.0b013e3181bee2f5

Helfrich CD, Simonetti JA, Clinton WL, et al. The Association of Team-Specific Workload and Staffing with Odds of Burnout Among VA Primary Care Team Members. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32(7):760–766. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4011-4

Creswell J. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Fourth. Sage Publications, Inc.; 2014. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/research-design/book237357. Accessed May 2, 2016.

Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Miller WL, Crabtree BF.Chapter 7: The Dance of Interpretation. In: Doing Qualitative Research. Second. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1999:127–143.

Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Addison R B. Chapter 8: A Grounded Hermeneutic Editing Approach. In: Doing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1999:145–161.

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software; Version 11. QSR International Pty Ltd.; 2015.

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) - Assessments, Tests| Mind Garden-Mind Garden. https://www.mindgarden.com/117-maslach-burnout-inventory. Accessed July 6, 2018.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42(2):377–381. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

Medicare C for, Baltimore MS 7500 SB, Usa M. program-guidance-and-specifications. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/program-guidance-and-specifications.html. Published August 24, 2017. Accessed October 4, 2017.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40(5):373–383.

Cohen D, McDaniel RR Jr, Crabtree BF, et al. A practice change model for quality improvement in primary care practice. J Healthc Manag Am Coll Healthc Exec 2004;49(3):155–168; discussion 169-170.

Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF, Etz RS, et al. Fidelity versus flexibility: translating evidence-based research into practice. Am J Prev Med 2008;35(5 Suppl):S381–389. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.005

Øvretveit J. Understanding the conditions for improvement: research to discover which context influences affect improvement success. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20(Suppl 1):i18-i23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs.2010.045955

Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T, Gold L. Methods for exploring implementation variation and local context within a cluster randomised community intervention trial. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58(9):788–793. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.014415

Jackson GL, Williams JW. Does PCMH “Work”?—The Need to Use Implementation Science to Make Sense of Conflicting Results. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(8):1369–1370. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2067

Reiss-Brennan B, Brunisholz KD, Dredge C, et al. Association of Integrated Team-Based Care With Health Care Quality, Utilization, and Cost. JAMA 2016;316(8):826–834. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.11232

Acknowledgements

These results were presented in part at the Society of General Internal Medicine national meeting in Washington, DC in April, 2017 and in Denver, CO in May, 2018.

Funding

Dr. Misra-Hebert is supported by an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant K08HS024128. Dr. Stange’s time was supported by a Clinical Research Professorship from the American Cancer Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Misra-Hebert has received research funding from the Merck Investigators Studies Program and from Novo Nordisk, both unrelated to this work. Drs. Perzynski, Rothberg, Hu, Aron, and Stange, and Ms. Fox., Mercer, and Liu report no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Misra-Hebert, A.D., Perzynski, A., Rothberg, M.B. et al. Implementing team-based primary care models: a mixed-methods comparative case study in a large, integrated health care system. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 1928–1936 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4611-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4611-7